If you haven't read William Gibson: Do it.

It's okay, I'll wait. Just pick up anything and start reading. The science fiction novelist who coined the term "cyberspace" continues to have a keen eye for the ways in which culture is driven by technological change. Recently I had the pleasure of reading a collection of his non-fiction works, published just last year, which illustrates this unique talent of his. Distrust That Particular Flavor is comprised of the various talks, book forwards, articles and essays that Gibson has published, however reluctantly, over the course of his career so far. One essay in particular (a speech, actually, given for Book Expo 2010) has left me thinking about The Future.

(cover, Urania 1959, Italy)

Not just the future as in our future, the time following the present, but "The Future" (with a capital "F," as Gibson puts it). The Future as in flying cars and moon colonies, where sky-scraping geodesic domes house cities of pure crystalline tomorrow. A leisure society where no one has to pull the levers of industry because the levers pull themselves. Where food comes in pill form. In a way, The Future was a promise made to us by science. I say "us," as in society, but I wasn't part of that "us," and I suspect neither were a certain number of you.

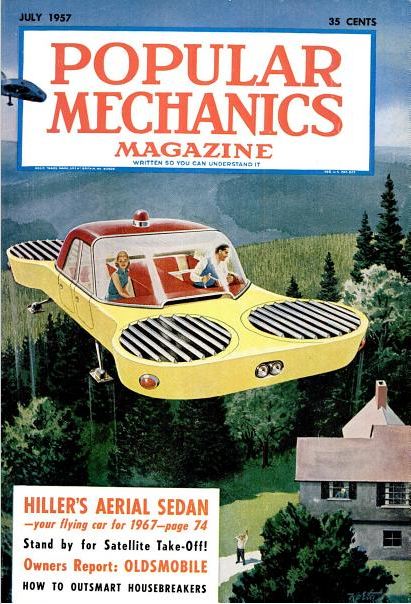

The "us" in question is my father's generation. Actually, he rode in on the last wave of a culture that might understand The Future (being born in '57). The War was over and America was hopeful that things were on the upswing, this before the Cold War nightmare had really settled in, and people were looking forward to the miracles of science that awaited them in the coming years. I've only experienced this second-hand - a general enthusiasm for the world of tomorrow passed on to me by my dad. He grew up reading (along with some classic science fiction) Popular Mechanics, a magazine that I still read today, and which has been publishing since 1902. I like to think of Popular Mechanics as filling the niche that Make Magazine currently fills but before the "Maker Movement."

Flying cars will always be The Future

Looking at the Popular Mechanics back catalog, I can see that my dad could've opened a 1979 issue (he'd be around my age) and read all about "The airplane that will explore Mars!" He may have seen U.S. Air Force ads beckoning him to "Be a pioneer in THE AGE OF SPACE!" My grandfather may have even had a 1957 issue around the house which advertised "Hiller's Aerial Sedan: Your Flying Car for 1967!" These fantastic sounding articles were printed side by side with more practical DIY advice about passive solar heat, how to install a roll bar in your car or how to make a child's go-kart. That's because they weren't "fantastic," they were just... spectacular.

None of this is to say that there wasn't a healthy skepticism surrounding these ideas, but there was also a certain popular futurism. People were genuinely pretty convinced that the scientists and engineers that had gotten them through the war and into space were going to continue to propel them into "tomorrow land," (or at the very least make their cars hover a little.) Similar stories printed now, Gibson points out, typically elicit a lukewarm response: "Oh sure," or "Huh, no kidding." The wonder isn't gone, it's just not part of the popular culture anymore. Gibson calls this "future fatigue," the antithesis of future shock. Technology has been advancing at a rate that's so amazing that we simply expect the impossible. Also, the amount of pure "stuff" that we're generating along the way has caused us to develop filters for innovation, a hardy cynicism that's eroding away at the wonders of "The Future." Not to mention recent history hasn't been kind to the notion that science and technology will ultimately make the world a better place: The A-bomb, biological and chemical weapons, climate change... we're really wreaking havoc with the tools we've developed.

There was another aspect to The Future, though. It wasn't only the belief that science and engineering would naturally better us as a society, but also the ability to imagine a specific world made better. The Future wasn't some nebulous concept of betterment, it was an actual place and it came through in full-on raygun technicolor, whiz-bang contraptions in tow. By some form of cultural telepathy I think we all know what each other is thinking about when we talk about The Future, as if it were a theme park or a distant country. Gibson talks about my generation, and the next even more so, experiencing an "endless now," where the future is basically now but with more stuff. I think it's easy to believe that progress will just happen, and that "the rest of us" don't have to worry about it; but I would argue that the popular notion of The Future, that sparkling tomorrow-land, was responsible for a large part of the technological advancements we saw in the last part of the 20th century. We had a goal and we were, all of us, working toward it (consciously or otherwise). When I try to imagine what "The Future" means now, I still see the bubble-domed flying cars of my father's generation. I don't know what today's "Future" is. There are glimpses in our speculative fiction of future worlds generally wrought with either oppressive surveillance or apocalyptic waste. When I say "I want to build a better world," I don't have a mental image to attach to the notion.

Assuming we need "The Future," how do we get it back? What can we do to instill that same wonder in the growing population of makers? Maybe we can pick up where we left off. We have a design language for The Future, albeit an outdated one, and it still captures the imagination. Maybe by revisiting the retro-future aesthetic, we can reignite that spark that we need to build our own ideal world. Can we really go back to the future, as it were?

This is a series of cardboard toys that I designed to play with that idea. Classic retro sci-fi shapes that come flat-packed. You can bring them to life with lithium coin cells and LEDs (both of which are decidedly more modern tech.) The response from people who notice them sitting on my desk has been really cool to see. Cardboard robot-men, rocketships and laser blasters (especially laser blasters) seem to ignite some part of the imagination in people that isn't accessible to, say, an Arduino. Certainly the Arduino is a lot more futuristic (in a literal sense) than the cardboard rocketship, but the rocketship is The Future. Hopefully toys like these can open a dialogue across the generational gap about what it was like to dream of The Future, and spawn the next group of futurists who will dream up their own "rocketships" or "robot men" (which could just as easily turn out to be Mars colonies and genetic engineering or hopefully something we can't even imagine right now). Come on, give us something to aspire to!

I know the Maker movement is already full of people who are working on disparate but equally amazing versions of The Future. I wouldn't want to downplay the missions of groups like Not Impossible Labs who are using that energy to really make positive change in the world; practical solutions to immediate problems are always an admirable goal, and it does us all a lot of good for people to think that way. However, we need some truly fantastic dreamers, as well, and a common language for talking about the future. It makes me hopeful to see events like Bay Area Maker Faire, which I was able to attend with some other SparkFunions recently, because it showcases the really bizarre and fantastic right beside the immediate and practical. There's a lot of potential in that mixing of ideas and I think that the community it represents (that's you guys/gals) is doing a lot to develop a modern idea of The Future. I think the Maker Faire is probably my generation's equivalent to the World's Fair, but more inclusive and more participative, which reflects the values of our generation... I think.

At any rate, I suppose I don't know whether my generation (or modern society as a whole) really needs The Future, and I certainly wouldn't pretend to speak for anyone else. A large part of what drives my work with SparkFun, though, is the hope that our customers will be the city planners of New Future, as I've taken to calling it. And looking at my watch, we're probably about due for a paradigm shift.

Let us know in the comments what you think about The Future: Do we need it? Do you remember it from "back then," and is it an overrated product of nostalgia? And also let me know if I'm talking out of my rear; I'm not usually prone to this level of seriousness and I'd love to find out that I'm just late for the train to New Future.

A quick addendum to today's post: You've been waiting patiently (where does the time go??), and the time is belatedly upon us: CAPTION CONTEST WINNER. You guys. Great showing this time; we get the feeling a lot of you have been waiting for the perfect combination that is embedded electronics and prehistoric fauna. But there can only be one winner, and that winner is Member #430268!

In the Jurassic Age, data was transferred in Mega Bites…

Congrats, member with string of numbers! $100 in SparkFun credit is coming your way!

It seems to me as if we as a society have become so wrapped up in instant gratification that we have stopped looking to the future the way we used to. And the collective enthusiasm we as a society once shared has been replaced by divisiveness. And even our entertainment - remember the thoughts and dreams that Star Trek inspired? - has been replaced with reality TV, which inspires absolutely no one to try to achieve anything great. I think one shining beacon of hope is Elon Musk. He imagined electric cars for everyone, refueled by free, solar-powered charging stations, as well as space flight the way we all pictured it - and has set about to making them a reality. I agree with you, it certainly is time for a paradigm shift. And i think that visionaries like Musk can help to re-inspire us to once again dream of and reach for The Future.

Thanks for that. I totally agree with you! Even I can't help but be cynical of Musk, but I couldn't tell you why. I'm psyched that he and a few others are doing big-time work on The Future. Maybe my cynicism is just another symptom of the underlying societal problem. At any rate, it's something I'm trying to change. Hopefully other people feel this way.

I think one of the issues with 'future tech' is that we've gotten to the point where we hit an analogy to the alien life dilemma (either it's there but it's too far away to get in contact with, or it's not there, so why worry about it?), with an added twist: alien life is already here.

Basically if you think of flying cars.. we know they can be done, but the regulation, severity of incidents, etc. would be a nightmare. We'd want them to autonomously fly-by-wire all nicely first, and before we go there, we need to do so on the ground first. That was 'future tech' 20 years ago, now Google's experiment is showing that it can and does work.

Not too long ago, replicators also seemed like science fiction. Nowadays, not only can you have 3D objects printed in a variety of materials, but for less than $500 you can have a 3D printer on your own desk. Sure, it's not quite like a resequencing of base material atoms into spacebooze, but between that and 3D printed organs we're making great strides. It's rapidly becoming less fiction and more fact.

Now take something like a holodeck, though. We can imagine all sorts of display technology, but scientists have no clue how to create a virtual object in mid-air that isn't also translucent and/or luminescent (projecting onto smoke/mist/dust particles, or by igniting the air itself into a plasma), never mind giving tactile feedback. A VR helmet and force feedback gloves are as close as you're going to get for the foreseeable future. So it's relegated to purely science fiction until somebody comes up with a feasible way to actually make this happen, and that might require a revolutionary new discovery first - which tend not to happen very often - or a completely different approach (rather than actually having a world created around you, just make the brain think there is). Until then, it's not really something people tend to think about nearly as much as flying cars were on people's mind a few decades ago, because it really does seem outside the realm of the possible - whereas flying cars have been known to be possible (remember the car that you'd just bolt wings onto?). It seems less science (fiction/fact) and more magic, and 'any sufficiently advanced technology ...' is only going to apply, and immediately self-destruct, when it's become reality.

If instead you think of a portable computer that you carry in a pocket and allows you to look up information no matter where you are.. well, we've already got that. The ability to take a photo and show it to your family half way across the world immediately? We're there. Create diamonds out of carbon dust? Been there, done that. Fly from Paris to New York in just a few hours? Had that, no longer have it, but we know it's possible at least and might be getting back to it.

tl;dr: The future is now, and we're generally far too cynical about the future-future to regain the euphoria of decades past. But there will always be people imagining new things, and people trying to make them a reality.

On the up side, you can at least find remote controlled flying cars, like the B (no endorsement, just coincidental recent launch).

I think you're right about this, but I'd like to think we can still abandon the cynical in exchange for the critical. The critical would be far less detrimental to The Future and has the benefit of not wantonly discarding good ideas while letting bad ones go unquestioned.

p.s. the 'B' looks awesome, I was just checking it out a couple of days ago. I'd love to fly one ;) (if the 'B' folks are reading)

The Future to me - at least the fantastic imaginative side of it - seems constrained to two realms decidedly outside of standard human perception: the very big and the very small.

The very big Future is stuff on a global scale and beyond our planet. Huge energy capturing devices like offshore wind turbines and the space ships of tomorrow that are in testing today. While some of these technologies are fathomable in comparison to my physical self (unlike, say, a massive solar sail...), these are technologies that will be deployed where I can't see them. Like in the middle of the ocean or out in space, not in my neighborhood (like the flying car) or holstered to my hip (like a laser blaster).

The very small Future is the feeling I get when I watch a program like the NOVA Making Stuff Series. Metamaterials that do amazing things. At human scale they look innocuous (perhaps with the exception of broad-spectrum invisibility material, which would look like whatever's behind it). These are the things that, when scaled up to human size, give us devices that behave like magic but we just expect them to work and go on with our lives. I've definitely fallen into that trap - it's a part of the human condition - but whenever I read about or see images of what's going on at the nano-scale level the amazement and wonder returns, because it is and will remain utterly outside of my experience.

This is where The Future of the past, like what you see inside the big ball at Epcot, falls flat. It was the The Future at human scale. But that's not where the truly astounding advances will happen. Especially if we ever plan on being a Type I Civilization or better - the scale imposed by our physiology is as limited as the chunk of the spectrum imposed by our organic eyeballs. We've explored it so thoroughly that what wonders remain uncovered are few and far between, though not absent. Our exploration of other scales is really only starting to heat up and that's where the best and most awe-inspiring advances of The Future lurk, waiting to be found and engaged.

In case I didn't make it clear in the article, science and technology weren't the only driving force for "The Future," We wouldn't have been able communicate any of those fantastic images without designers, artists and writers who were doing equally advanced work. So don't forget the 'A' in 'STEAM'

You're not kidding about "expecting the impossible". I showed my Mom my iPad (she's a grandma now). I tried to relay to her the amazing-ness of the technology and how much tech is crammed into such a tiny space. From the retina display, to the camera, to the internet connectivity. When you really think about it, when you take the time to think about all the technology that makes it possible, it's amazing any of it even works at all! I tried to impress on my Mom how amazing technology is and can we image where we'll be in 10 years? She just said, "Meh. But isn't it supposed to do all that?" Totally not impressed. Maybe she just doesn't get it. I'd show her Avatar and again, not impressed. "Isn't it supposed to look that good?" Maybe it's just my Mom but she's not impressed by technology at all.

In a way, that's a success of marketing. People have been told not to worry about the technology underlying their favorite products or experiences because it'll 'just work.' I think it's probably due to some very clever design and engineering that (most of the time) these things really do 'just work.' Unfortunately, it may work too well...

And in the end, this could be why The Future went away. Advertising has created consumer expectations that are too immediate to be served by what the public mainly regards as wish-thinking. Most people are convinced that we're already living in The Future, so "if it isn't on the market now, it probably never will be."

This is actually pretty evident, now that I think about it, in the popular lament of "Where's my flying car?" Instead of feeling as though we're close to, or finally learning to approach, The Future of the 60s, We act as though we're already in The Future and it just turned out differently than we thought it would. We're not there yet, we never should be, that's the point.

Thus my attraction to the Maker Movement and to the ideals represented by OSHW and OS. Instead of declaring it The Future and sitting on their patents, these communities are forcing themselves to continuously innovate. And unlike previous wishy-washy ideas about freedom, this one is actually driven by capitalism which seems to come naturally to most people (we can have that argument later) and is compatible with our economy such as it is. So, for better or worse, it will probably continue into the foreseeable future.

Thanks for reading!

Nostalgia ain't what it used to be!

pepperidge farms remembers...

Aw, I remember when I used to be nostalgic...

"The Future" was provided to me by a TV show called "Beyond 2000"... Im still waiting for it.

I think "The Future" will come after OUR generation finishes harvesting all the "Yak Fur".

We are the ones building the technical foundation, 8 bits at a time, for that ever elusive "Future".

We got the Future, and have more Future yet to come. ...for certain values of "We". The optimism is the part that we're a little short on.

I think the big difference is political. The generation outlining the Future above had a slightly difference context. 1935: social security established, 1938: a 40-hour/5-day work week established, 1945: the most effectively aggressive fascists the world could recall were defeated (classifying the Mongol invasion as oligarchic), somewhere in there the Great Depression was overcome. This have a natural optimism that progress in technology would be used to the benefit of the whole, with the specific inventors and manufacturers rewarded, but not to the detriment of others. They expected to have to be a bit politically active to get what was needed done, and to keep politics honest. It even made it into the parenting guides of the time (see Dr. Spock's introduction on the responsibility of parents).

Since then, as near as I can tell, the cultural emphasis in a lot of business and politics caught a case of Machiavelli and shifted from being better, to being cheaper. We had both before, and we still have both now, but the emphasis... there is a bit more of the stench of stagnation, as last years winners try to keep this years kids from creating any new competition. Increasing productivity became a way for the largest companies to give workers less instead of growing more, and the leisure promised by technology was replaced with a combination of the longest workweeks in the western world and higher unemployment. A lot more people seem to have taken to calling politics dirty and not keeping after the politicians to keep citizens interests in mind.

It's a shift though, not a total change. The makers and open sourcers really show the alternative here. It goes back to competition to be best in the context of working together, and contributing back to the society that gave us the hand up in the first place, and trying to contain and overcome Machiavellian competition. Whether the old school credit unions and distributed manufacturing with drill presses, or the nouveau hackerspaces and distributed manufacturing with soldering irons, the same "we can do it (but I can do it better!)" attitude is still the road to a great Future.

The makers are still trying to help out the huddled masses, instead of focusing on fencing them out. This is the kind of greatness that, combined with some absolutely amazing tech, makes for a future with the kind of awesome that we can eagerly anticipate.

Avoiding the dystopian nightmares we've had for decades? Keep after your politicians and don't expect it to be particularly easy. We've already slipped to the point of having "free speech zone" cages at many major speeches for the last decade or so, and the internal surveillance... there's some work to do. This is where having a Future that we can clearly imagine and really look forward to becomes important. Without it, it's a lot harder to keep up the work needed to maintain a nation that's a really great place to live.

And flying cars? I'm OK waiting - 3D printed bone replacements and minimally invasive heart surgery are a fine start. And when do I send in the tissue sample to have spare organs on demand as I age?

Hear, Hear! That seems like a totally fair assessment!

Science fiction has tended to be too optimistic in some places, and not optimistic enough in others. But sometimes they got it right. In the very first foundation novel published back in the 50's Asimov predicted the pocket calculator. He was probably the only author that ever got THAT one right. Some future predictions were right on technically, but not practical or too dangerous in reality. Personal helicoptors were long seen as the future, but the vision failed due to the expense of the machines and how difficult they are to fly! Not every fixed wing pilot makes the transistion to rotor wing, because it takes talent (and lots of expensive hours in type)!

Back in the 50's and 60's the fear was we'd destory ourselves in a big atomic blast. Now we worry that we'll simply slowly make the planet unable to support our species life kind and number. We've also come to realize just how lucky we've been not to have been wiped out by a rouge rock from space, or a super volcano eruption. So maybe we've tamed our vision of the future somewhat because we are now afraid that there might not be one.

There are two forces working against "the future": economics and education. Economics means the benefits of the new technology must outweigh the costs. Take self-opening doors, for example. We've had the technology for that since before I was born, but no one has it at their home, because the alternative is simpler, cheaper, and meets our needs just fine. Where is the technology used? Where the benefits outweigh the costs: at stores where you need to push a cart through the doors, and where it helps people with wheelchairs get around more easily. Same goes for flying cars, or ubiquitous electric cars. We've had the technology for a while that makes it possible, but it won't become widespread until it is cheaper, safer, and more convenient than what we've got.

The other factor is education. Every once in a while Star Trek will show a junior high student complaining about calculus and warp core theory. The presumption is new technologies will get pushed earlier and earlier into curricula, but that is happening extremely slowly, if at all in real life.

If they're lucky, kids will get some basic education in using computers as an office tool: writing papers, doing research, making presentations, etc. The programming knowledge needed to advance the technology is still only taught at an extremely basic level until you get to college. Electronics teaching is practically non-existent in our elementary and secondary school systems, even though kids have the aptitude for it at relatively early ages. What education does happen is done almost exclusively as extra-curricular activities. It's a travesty that most kids graduate high school without even doing something as simple as blinking an LED using an Arduino.

The unfortunate result is the maker movement is largely inaccessible to people unless you have post-secondary education in it, or you personally know a maker who can mentor you, or you are extremely motivated to teach yourself using the Internet.

Growing up, I remember many of these "futurisms." But I was looking at ten- and twenty-year-old magazines. I was living in that future, and those things didn't exist. So early on I became jaded.

As I grew up, I discovered I was wrong. Some of these magical things did, in fact, exist. Very few of them were in those magazines, however. More of them followed from period literature (pocket calculators and geosynchronous satellites) than from gaudier magazines. So I began to read with an active filter, looking at what could actually be done, and how new products from engineering journals could enable the dream products of yesteryear. I tried building things that worked, rather than simply dreaming about them, and found out how hard that really is.

These days I've joined a local hacker-space. I have a background in electronic hardware and cloud computing, and I look at projects the group wants to engage with an eye to, "how can we make this happen with available technology?" I used to dream about the future and how technology could make the future happen; now I live in the future and make it happen every day.

Close enough.

I spent a large part of my childhood in one of the epicenters of The Future. My father worked on the Apollo program at the Cape, and we used to watch Gemini launches from our backyard; when a launch happened during the school day, classes at my grade school stopped and we watched the launch from the soccer field).

I used to devour books by Heinlein, Norton, Asimov, and all the "golden age" pulp I could find. I went to college with the specific goal of becoming an astronaut; I remember being worried when I entered college that I'd be too late to be on the first Mars mission.

Beleive me, I've been quite aware of the passing of The Future. I think of The Future as a close friend, one that I miss dearly. For years, I've been astonished at how much things have changed. My generation was excited about The Future, my kids generation was terrified of it. We were going to go out into space and eliminate poverty, crime, war and disease; my kids are going to see the world die from everything ranging from nuclear winter to global warming.

In my opinion, The Future didn't just die, it was an act of deliberate murder. The Future had to be done in because (a) the entertainment/media complex realized that scared people generate better ratings than optimistic people, and (b) the politicians realized that a frightened population was easier to control than an optimistic one. Add to this mix a multi-billion-dollar environmental industry that survives only by scaring the bejebus out of people and an "alternative" energy industry that seems to exist only to transport taxpayer money into the pockets of the politically well-connected (with a reasonable portion going back into political contributions)

What we have in place of The Future today is a self-sustaining system that transforms fear into money and power and then back into fear. And the people who profit from it aren't going to let it go away anytime soon.

I grew up on Golden Age SF too, though in the 80s and 90s midwest a long ways from the visible machinery of the space program. The stuff is baked pretty deeply into how I understand the world.

It seems to me like a lot of this discussion misses the ambivalence and awareness of potential catastrophe that's always been an important strain in SF, and a major determinant in so much of it. Heinlein, Asimov, Clarke, the stuff in the classic Groff Conklin anthologies, Bradbury, Bester, Herbert, Zelazny, PK Dick, Niven, Lester del Rey, Ursula Le Guin, Lovecraft, Spider Robinson, Orwell, Haldeman, Harry Harrison, John Brunner, David Brin... These people worked at very different times and places in the cultural landscape, but to me as a kid they were all part of the same conversation, and it was a conversation with some really somber themes just as often as it was one defined by anything like triumphalist futurism.

Even guys like Heinlein and Asimov wrote a lot of futures conditioned by human inability to transcend our worst failings. Children of the 80s grew up with the near-inevitability of a massive, world-crippling nuclear exchange as part of the cultural background radiation in part because it had been so thoroughly explored in the literature of the imagination since at least the end of WWII. (Hell, Heinlein wrote "Solution Unsatisfactory" in 1940.)

I guess I don't really share the sense that the capital-F Future has gone away. I'm as nostalgic for a certain vision of it as anyone, and there are a lot of things we could stand to recapture. It's maddening in particular the extent to which our culture has turned its back on a serious discussion of space. But I'm also constantly struck by how SFnal the present we occupy has become: How many times in a given week you can look around go "well, it's the Science Fiction Future now". Which is sometimes exhilarating and sometimes terrifying and sometimes both. The trick is that there was never only one such Future, and the one we happen to be occupying looks more like the ones Gibson was writing in the early 80s than it does a lot of the alternatives. ("We're all living in a William Gibson novel" has become such a commonplace over the last few years that I couldn't even tell you approximately where I first heard it. The idea is everywhere.)

I'm consistently amazed at the level of enviroskepticism people bring to the comments here, though maybe I shouldn't be. I don't want to suggest that there aren't plenty of people making money off of seedy greenwashing and general "buy this in compensation for your sins against the planet!" undertakings, but for a major subset of educated, technically-minded people to treat concerns about the health of the only biosphere we've got as simple fearmongering is not doing anyone any favors. I'm worried in part because a literature obsessed with the future gave me a framework for understanding that technological decisions have consequences, that the status quo never lasts, that the timescale of an individual human life is minute in comparison to the vast sweep of history, and that the extraordinary - for better or worse - can and will happen.

"I’m consistently amazed at the level of enviroskepticism people bring to the comments here..."

It's not just here, Brennen. I see it on comment areas that have a libertarian bent a lot. Now, to be totally fair... some of the "enviroskepticism" is on fairly sound turf, like the comment earlier directed at me pointing out that nuclear power plants have a good safety record when you factor in all aspects of the environmental impact of power plants in general. It's true... radiation leaks occur, but it can't possibly compare to the radiation dumped into the Pacific Ocean when the US was testing nuclear weapons there. The US set off hundreds of nukes there in the process of "perfecting" the system, if that didn't utterly destroy the environment, what will? And that was just in the Pacific Ocean... many more were underground tests.

What dismays me is the short sighted stupidity of central policy. Take yellow dent corn, the GMO poster child raised everywhere in the "Bread Basket" of the US. It has two primary GMO traits, Glyphosate (Roundup) resistance and ignorance to overcrowding. The Roundup one is obvious, the overcrowding one is not. Basically, this corn can be planted 4 times more densely than normal, the plants will not "crowd each other out" as natural plants would. This requires the use of 4 times more seed per acre, 4 times more water, and 4 times more fertilizer. It also allows central policy setters to reduce the "price" of corn such that without the 4X yield, you cannot survive. In the immortal words of Han Solo, "It's a trap!"

Add to that the partially fossil nature of the Ogallala aquifer that we're draining to water all that corn, and you have an upcoming disaster. Sure, that disaster happened before, during the "Dust Bowl", but there were far fewer mouths to feed then, and most food still came from local sources at the time. And yet, a lot of people in libertarian circles will defend GMO crops.

Note: I'm not singling out libertarians. I just happen to hang out with them a lot, and I've noticed the "enviroskepticism" when it comes to GMOs.

Technically the warming alarmists are the skeptics. They have not done a good job of convincing a very large portion of the scientific community that they are on to a serious problem.

Your food concerns are a good example of being scared of the future without taking in the big picture. With a good solid near term global warming, the tundra will be the new corn belt, and it is a LOT bigger! (My gosh, did he say that!)

OK, I'll stop. Well, except why would you add underground tests to your radiation total? And how much radon and other radio-nucleides are put in the air by coal plants world wide? By the way, one result of all the bomb testing is that the optimal altitude for an air-burst is above that which pulls ground debris into the fireball and neutron activates it. The optimal blast (from a pressure wave damage aspect) leaves very little radioactive material and none of what was called fallout. Then along came target hardening which requires lower altitude and the lower the altitude the more fallout till it gets really dangerous. By dangerous I mean to say a hemisphere as opposed to the destruction of a fixed target, like the fire bombings of Dresden or Tokyo. Anyway, as a source of environmental radiation I put US testing (or Russian testing of huge devices on land) pretty low on the present scale. The US testing over water must have made a lot of sodium 22, but who can be upset with a positron emitter!

The Soviets used to test underground on Novya Zemla all the time. I could pick up their distinctive signature on a seismograph pretty easily. Today they run nuclear powered ice breakers in the region. When I was a kid in the 60's, Scientific American had a project where you put scotch tape sticky side up outside for a day and put it under your Geiger counter and looked for increases with exposure - the idea being you were picking up some fallout.

There is, I suppose, very little point in throwing any more fuel on the Standard Climate Flamewar here. Somebody needs to write a climate-shouting-match version of Hipster Ipsum and we can just build a feature in the comment system that just links there past a certain distance into the usual back-and-forth.

Ok, so I never farmed, but large-scale agriculture conditioned pretty much every aspect of my life for the first couple of decades. A lot of my family still make their living either farming or in agribusiness, working for really enormous companies in chemicals, seed, ag finance, and mechanization. My house is still full of random swag with names like Ciba, Novartis, and Bayer on it.

I'm not concerned about the long-term impacts of current agricultural practices (including the rollout of GMO crops) because I'm lacking perspective on the system as a whole, or because I think there's an intrinsic evil to gene hacking, or because I'm under any illusions that industrial ag as it stands could be dismantled without causing mass starvation. I'm concerned because I've spent my life watching the landscape change, chemical inputs escalate, water demand explode, yields balloon, most of the small operators get driven out of the business, and major corporations consolidate a truly staggering amount of power. I'm concerned because I know something of the history of the American Great Plains, and because when I look out the window of an airplane I see those telltale pivot irrigation circles splattered across terrain that just barely manages to support dried up grass and scruffy antelope without significant human intervention.

The food system is unfathomably vast, full of perverse incentives for most of its important actors, and has transformed much of the surface of the planet in really profound ways over the last hundred years. People with concerns about where this might all be headed don't always have all the relevant facts and often don't have enough of a handle on the technosocial reality of agriculture, but I'm comfortable extending them some sympathy.

Most of my family has been involved in either wheat/barley/lentils or timber. The timber is interesting. The people who came to ares like Aberdeen, Washington (Home of Nirvana) had a choice. They could harvest millions of salmon every year, or cut down the incredible forest once. Since salmon was "Indian food", they cut the watersheds.

On the wheat side, in places like the Palouse, the big agribusiness consolidations have not happened. How much do you think the ethanol and other subsidies have influenced what you have seen? Turning food into expensive fuel. Brilliant! Few things irk me more than seeing that "up to 10% ethanol" sign on a fuel pump. I would back a law requiring fuel for cars be sold like fuel for jets - by the pound.

But I was really just kidding and imagining the incredible land area of northern Canada and Siberia as farmable.

There are some aspects of the green/renewable/appropriate/sustainable/(insert insinuating term of choice) indoctrination that give me the same sinking feeling I get when I see yet another generation of physicists waste themselves on string theory. If what we expect to be the best minds can't avoid an obvious dead-end, how can we think the climate scientists and engineers (and the semi-literate Earth-Dayers who are both acolytes and controllers of purse strings) are on the right track? So much of this is peer group competition that it is like an isolated valley in New Guinea. The reason they pursue the goals they pursue is lost in the past. All they know is the way to rise in the group and win mates or garner status. Lets just say I am more suspicious than skeptical. I lived down the street from the guys who started Earth Day in Palo Alto (you could look like an army of earnest junior scientists back then with a FAX machine in a closet and the right list of phone numbers) and I studied cultural anthropology before physics. The causes of a pool of consensus in the sea of researchers related to climate are many and the most influential do not need to be scientific. Just look at the faculty of a modern elite university!

IMHO I think we've become to risk adverse, we don't pursue bold dreams because it just may not happen. Some talk themselves out of it, so never even try. Also we don't reward thinking differently, we shun those who do.

Maybe the future could start here:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W2FPZrbYWK0#t=90m05s

I think that at the moment (and this is my personal opinion) that we /are/ actually making some serious scientific headway, just not in such large scales as going to the moon. We've got things like a high-speed camera that can see light move, a group of uni researchers who have made a 3D printer capable of creating whole new molecular structures. We don't perhaps have the vision that those in the previous generation had, but then again society has changed dramatically. A lot of the issues that we thought we would never solve actually have been solved, perhaps with less dramatic solutions than originally thought. And while I might have been a bit disappointed that Gangnam Style got more views than the Mars landing, I still believe that the populace in general is very excited about science and innovation. One must also not forget the Internet, which for me has become less of an "Oh, that's cool" to what really defines the human progress. The fact that we have created this network so you could, say, send the design for those cardboard figures to me in a few hundred milliseconds is, personally, mind boggling, and would certainly make some headlines.

I suppose my point is kind of what Bill Gates said about flying cars: "Are you sure you really want them? Flying is a really inefficient method of transportation." (This is, of course, all open to discussion.)

Nick (sorry), great article.

There are a few things we "know" about the future: population growth will continue exponentially, the processing power of computers will get faster, smaller, cheaper (despite the thermal transfer barriers of silicon), the world will be simultaneously fracturing and homogenizing (Jihad vs. McWorld). Natural resources will become scarcer. Corporations will gain more power.

Other than that, I see the future as a blank page. I say, write your own.

Exponential population growth? Agreed, for bacteria. Birth rates are flattening out practically everywhere for humans. Prediction of human birth rates were the driving ideas of the doomsayers of the 1960's and 70's. They were so wrong that their books are hilarious yet the ideas have stuck. The same predictions were made about resources, yet proven oil reserves are greater now than ever and I would bet humans have not dug into more than an inch or two of the surface of the Earth. On the other side of the humpularity resources increase with time.

(I thought they were both Nates)

Nope I'm a Nick, no offense taken. You have to click through to my profile to find that out.

Hmm. You're the second person that attributed the article to Nate. I'm pretty sure Nick Poole wrote it (I think this because it says so at the top.)

Heh. McWorld. I gotta remember that one.

Corrected, sorry Nick!

I think "The Future" cracked when people realized that technological advancements had consequences. Back in the 60's, it was just assumed that nuclear power could be made super safe and easy to use. People believed that Pharmaceutical Companies had their best interest at heart and would only make safe drugs that people actually needed. It didn't dawn on anyone that creating synthetic foods could go wrong.

Technology could do no wrong after building a nuclear submarine and sending people into space. Then the bills started to come due and the possible ramifications came to light. Now it's in your face. Nuclear plants fail and leak huge amounts of radiation. Engineered food ingredients like "High Fructose Corn Syrup" and "Partially hydrogenated Oils" were probably not our best ideas.

Not to mention the social issues.... what will a population of people without jobs to tire them out DO with all their free time?

", it was just assumed that nuclear power could be made super safe and easy to use."

Well to play a bit of devils advocate, there has been very few deaths due to 'leaking reactors' or nuclear energy plants in whole. It has been one of the safest forms of power generation than any other.

FastCompany has a good article on just how many lives have been saved due to nuclear power;

http://www.fastcoexist.com/1681759/forget-fukushima-nuclear-power-has-saved-18-million-lives

HF Corn Syrup was a policy failure more than a failure of food science (see: corn subsidies) But your point is valid. I'd argue only that for every innovation of the time that has caused catastrophe, there are probably ten that we couldn't live without. We just don't think about the positive things because good tech is invisible.

You might be on to something though, I think we'll probably go through a pragmatic clean-up period before another few decades of rampant innovation wash over us.

And you're social issue is a tough one. The leisure society has always been a stumbling block for futurists, mostly because it boils down to the existential question.

"I think we’ll probably go through a pragmatic clean-up period before another few decades of rampant innovation wash over us."

I think that's a very positive view. I think I'll try to direct my own thinking along that line, as the logical extension (To my dismay.) of the current western society is a "The Future" with a highly totalitarian social structure. A high technology future, to be certain, but a future where your activities are an open book, and where a lot of young people full of energy to use work in Law Enforcement and NSA style data collection.

Well, they had those concerns in the 40s and 50s as well (When Orwell wrote 1984, he was really writing about 1948) although I'm not entirely certain we dodged that bullet. Luckily, young people full of energy hasn't been working out as well for the old guard lately as they might have liked (See: Snowden and Manning) Maybe today's whistleblowers will be tomorrow's NSA-dismantling heads of state.

At any rate, that's just my opinion and I tend toward the optimistic.

Actually, Nick, young people full of energy have been working out great for the "Old Guard" per se. For every Manning or Snowden there are hundreds of thousands that love the job. Sure, it's a potential issue when a whistle blower pops up, but those events also show the potential "loyalists" in society that they are being watched, and had best stay in line.

Organizations like the NSA cannot be dismantled without severe political fallout. Think of all the jobs that would be lost! These organizations just get bigger and bigger.

Anyway! I'm not trying to bring you down, here. I would love to see a utopian, libertarian style future where we all have nothing better to do than to engage in engineering projects that better all mankind. But unfortunately, we're all a bunch of evolved apes, many of which think in Machiavellian terms.

The future's great, but we also gotta live in the here and now. And with the way things are going now, the future is being made 'here and now'. (I'd still love to see the future though...)

Lot of Heavy thinkers on the comments link today. Guess I get to be the shallow one. Dude! Where can I get those cool cardboard toys! Those have a lot of potential for fun. Heheh.

Hahaha, hey at least you're participating! ;)

Glad you like them!

Well, they got spotted by Nate sitting on my desk and they're on their way to "productization" so you'll be able to buy them from us soon. The vector files will be available as well if you have access to a laser cutter (or a good hand and a hobby knife)

Very interesting piece Nate. I am from the generation with the Future vision. I have taught high school physics and math in the last 10 year and I could see that my students rarely shared my vision of the Future with a capital F. In some ways they are more realistic. I was convinced at 18 (Moon landings were becoming routine) that I would have a job on the Moon by the time I was 35. The next step focus was on large space habitats though, not the Mars fixation that NASA has today. The consensus was stated this way "why would you climb out of one gravity well just to go down another?". I still agree.

The Popular Mechanics/Popular Science/Popular Electronics versus Make comparison is also telling. To me, Make is like kids books with little more challenging than drilling a hole in your cardboard tube magic wand with a light bulb on the end. When you look back at the 70's you see projects that if compared to today would have to be things like home made quantum computers or garage jet aircraft or large particle accelerators - in fact there were DIY atom smashers in Scientific American in the 60's.

One of the features of the Future was the diminishing significance of the cities. The flying cars and garbage can sized nuclear power sources allowed the notion of living anywhere and no need to be physically connected by roads and buildings. Think "The Naked Sun" versus "The Caves of Steel". The trend was toward the open space. But in reality there has been a steady drive towards citification and making cities more attractive. The steady shift in population shows the success of this.

I think you can find a fundamental difference, one I found with my students. In the Future, the individual has huge amounts of energy available for personal use and the more the better. It is what makes all things possible. Today this is seen more as gluttony and dangerous or somehow destroying "the planet". There is a sense of shame attached to what is seen by many as waste. Lick the cheap abundant energy problem and maybe the Future will be back in vogue.

Here is a good example of the generational difference. In class, if I threw a Mountain Dew Bottle and hit the waste basket instead of the recycling, the students would exclaim "Don't you know it takes 10,000 years for that to break down in a land fill?" I would look at them in wonder and ask "Why do you care? It is buried in a land fill! Where do you think it came from in the first place?". What do you suppose is the source of their outrage? They were so well programmed by the time I got them that critical thinking on some subjects was simply impossible. There have some very strong taboos.

On the other hand, I have seen the impressive low costs for Space-X to put big masses into high orbit, and If I won the lottery the capital F Future would be back! At least for me and my team.

That's a pretty interesting viewpoint, actually. I'm annoyed (as you appear to be) at the trend of popular wisdom parading as concern or responsibility. It's very fashionable to be eco-friendly but without understanding why, you're defeating the point (which is to be more conscious of your impact) I should say, however, that your example is really weak (and, frankly, a little troubling) because they absolutely should care about recycling. People should be able to think critically, even about those subjects which are in vogue, but critical thought applied to recycling still shows that it's a good idea (although, when it comes to glass, you might be able to argue otherwise because of the energy cost of processing it)

That being said, you're right and wrong about Make. While they do try to keep things simple, they've also showcased some pretty impressively complex projects in the past. I had to get over this myself, because I grew up using a step-stool to reach the radial arm saw and anxiously awaiting my next issue of Edmund Scientific. But what I realized is that the reason the older magazines seem...let's say: sturdier... now is because they were forced to use the tools and materials that people had access to. Those tools and materials have changed, for better or worse, so Make meets their audience on different terms.

It should be mentioned as well that I don't mean to suggest that Make has replaced PopSci or PopMech in any way, after all those publications still exist. I just meant to point out that the people who read PopMech at the middle of the century are the audience that Make seeks to serve now.

I agree with you partially about cities as well. For all the monolithic crystal cities there were also nuclear prairie homes. The drive toward urbanization is a force to be reckoned with and it's had a huge impact on our culture. Although I do think it's a natural side effect of capitalism and not a necessarily unpleasant one so long as we apply our technology to city planning. And as long as we don't disenfranchise people who want to own land outside of the urban zone by letting it get developed into hip country housing.

Space-X is an awesome project and I'm really happy to see private space working out so far (for all of the discouraging words from people who know the space industry) I know the moon feeling, I'm glad to say, because reading about the MarsOne project made me hopeful that I might not die on this planet (beautiful as it is) And that's a feeling that really drives private space endeavors so I think it's important to inspire that in people.

The one thing I agree with you about wholeheartedly is that people need access to cheap, plentiful (and I would add responsible) energy. There is justified shame associated with burning tons of limited fuel on something that isn't assured which makes innovation hard because risk is so bound up in the process. At the same time, regardless of how annoying kids can be when they parrot pro-planet rhetoric that they don't understand, no thinking person can look at the data and deny that we're gonna be in trouble if we don't fix our energy use. Believe me, I was a late-comer to the climate debate but I was finally convinced.

Woo, anyway,

Thanks for reading, and thanks for the insight!

I am not as highly sensitized to minor recycling partly due to the matter of scale. How many water bottles do you think are made from 1 cubic meter of the raw material? (A truck tanker load worth would be a ridiculously large number).

There is also a generational difference you can see in writing style. When you say "as long as we don’t disenfranchise people who want to own land outside of the urban zone by letting it get developed into hip country housing" I am sure it seems like a very reasonable concern and is common in your cohort and I understand what you are saying. But the people I know who are my age would read that as politically charged, as if you or the "we" own all the land and get to decide who and how it is used. And in my parents generation they would not dream of imposing their will on someone else. I don't know any of them who could form that statement. They just don't think that way. Maybe it is a matter of crowding or the effect of living in the West with so much open space and so much "owned" by the government, which we think of as us. Though I have a younger brother who thinks the whole country should be a national park. He has been at Jenny Lake Rescue in the Tetons for the last 20 years and doesn't even like the tourists treading the meadows in his park. But I ramble (I can get you some tips on climbing and lightning).

I started writing to say I think we need to consider that use of oil and gas and nuclear may be needed in very large amounts and as cheaply as possible in order to get over a technology hump to a future with something better and cleaner. (The Humpularity - if Vernon Vinge can name the obvious, so can I :-). It worries me a lot that we might be strangling industry and economic growth at exactly the point where we need it most. What if we drain the momentum needed to get over this potential and there is only one chance? You can extrapolate from there.

I know there is a lot of interest in great floating wind farms and other alternatives. I fear they are like the Moon promises of the 60's. So far they fail. I won't go into details, but both land and sea systems are failing miserably. Like 20% of starting energy production after only 12 years on land and 7 years at sea. You can't even pay for them in that time. I don't think they can take us over the hump. I worked with a lot of radiation as a physicist. I am in no way casual about it, but in the grand scheme of things I am not particularly worried about power plants and there ARE safe nuclear reactors. In fact some great new designs that produce virtually no waste except the reactor casing itself, which will be pretty hot after 100 years and I suspect get some brittle metal problems. It is all neutron activation though and pretty short half lives. I wish the U.S. was not allergic to them.

I agree about Nuclear. I cringed when I heard about Fukushima Daiichi exactly because I knew it would leave a bad taste in people's mouths in regard to nuclear power. By no means should we rebuild the old reactors but I do think that a fresh perspective on nuclear could get us over the hump... or through the humpularity (I like that one)

As for your generational rant, I totally get it. But I assure you that it's mainly a difference in writing style and not political philosophy. When you say your parents generation wouldn't dream of imposing their will on anyone, you're slightly wrong. Because they were free citizens of a democratic republic and thus imposed the will of the majority. Not that there's anything wrong with this, but it's the reality of things. The "we" to which I refer is the citizenry. When I say, "as long as we don’t disenfranchise people who want to own land outside of the urban zone by letting it get developed into hip country housing" I don't mean to imply that any part of that land is "publicly owned" (a rampantly abused form of ownership as-is) but simply to imply that "we" (the people, as it were) don't lose sight of the idea that the city shouldn't sprawl out and envelope everything so that we can make political decisions that are least likely to put people in power at the civic level who might approve every development application and at the national level who might seek to make those lands outside the urban zone public.

It's easy to project on my generation, because the generation that preceded us proposes to speak for us: in advertising to us, making our television and sculpting our pop culture. But I can tell you that a lot of us would be happier with a lot less hand-holding in the form of an overgrown federal government.

In case anyone reads these threads as they age, take a look at a pair of books that I think really define a version of The Future as seen from the 1970's / 80's. They are by physicist Gerard O'Neill (I think he also wrote an interesting text book on particle physics) The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, also a NASA conference proceedings "Space Settlements: A Design Study ". And one by T. A. Heppenheimer. "Colonies in Space". Not to be confused with "Pigs in Space!" and one can not neglect "Space-Based Manufacturing from Nonterrestrial Materials, Volume 57 Progress in Astronautics ans Aeronautics" also O'Neill. Between talking to these guys and Robert Forward I figured out how to measure the speed of gravity and how to soft land on the Moon without rockets back in the early 70's.

The colonies books have some really cool stuff like windows that pass all the visible light and block radiation with any thickness of solid opaque material you want. Give that one a try before reading :-)

Inspiring post. I am excited to see so many cool things being made now. due to the internet the opportunity for people to quickly learn, whatever they want, has never been greater. I want to see more of people make things, instead of innovation being locked in government or corporate R and D departments. I believe that the more innovating and exploring people do, in areas from mycology to flying autonomous vehicles, the more people will understand it and hopefully want to use it in good ways. I still have that gleam in my eye, when I think about the Future; but even more I would like to see, a future created by everyone! A future where we still work toward the future.