Gladys West is an American mathematician who made significant contributions to the development of the Global Positioning System by developing a complex model of the Earth, and you may not have heard of her even though you use the technology she helped develop every day.

West was born on October 27, 1930, in Sutherland, Virginia and was one of seven siblings. Her family owned a small farm that she worked on as a child, and she knew growing up that education would be her ticket to a world outside farming. Her family couldn't afford college tuition, but she graduated valedictorian of her high school in 1948 and received a full-ride scholarship to Virginia State College (now known as Virginia State University), a historically black public university. West graduated in 1952 with a Bachelor's of Science in mathematics, and came back to complete her Master's in mathematics in 1955 after teaching math and science for a few years.

Source: Hackaday

Beginning in 1956, West worked at what is now called the Naval Surface Warfare Center in Dahlgren, Virginia. When she was hired, she was the second black woman ever hired and one of only four black employees. Throughout her time there, the Civil Rights movement was in full swing and she encountered many hardships because of racism, primarily seen in the lack of recognition she received for her work, while her white colleagues received praise and additional privileges.

Dr. Gladys Mae West and her husband, Ira West, one of the other few black colleagues she worked with at Dahlgren. Source: U.S. Navy

She worked in the Dahlgren Division as a programmer for large-scale computers and managed projects that analyzed data from satellites. She worked on a variety of cutting-edge mathematical problems there, from proving the regularity of Pluto's moon Charon relative to Neptune to working on the first satellite that could remotely sense oceans. It was here that she did the work that would lead to the Global Positioning System.

Gladys West and Sam Smith look over data from the Global Positioning System at Dahlgren in 1985

Like a lot of technological innovations in American (and world) history, GPS was born with military applications in mind. Earlier systems for navigation weren't precise enough, and while certain technological predecessors like LORAN and Transit were being used in the 1960s, the Department of Defense needed something that worked quickly and accurately.

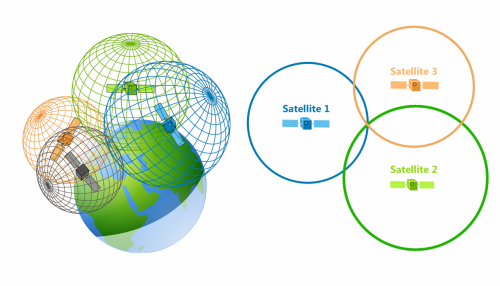

GPS works by using a network of satellites orbiting the Earth to determine the location of a GPS receiver. The GPS receiver receives a signal from the satellites containing their current time and location data. The receiver uses the signals from multiple satellites to trilaterate its precise position on the Earth's surface by calculating the time differences between the signals.

Trilateration uses three distances to pinpoint an exact location. Source: GISGeography

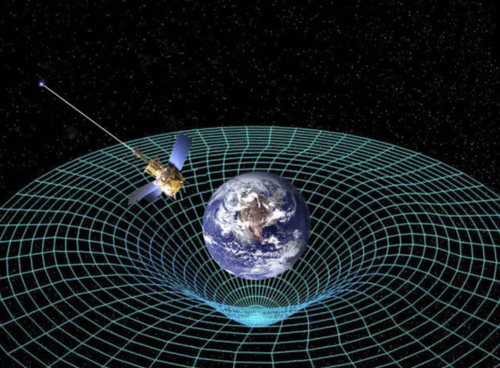

In order for this system to work properly, there are two big obstacles the creators needed to address. First, relativity. Up in middle Earth orbit, these satellites are moving at high speeds of around 13,900 kilometers per hour (8,600 mph), where time dilation can cause sizable errors. Meanwhile, those of us on Earth's surface are moving along with its rotation, which ranges from around 1,670 km/hr (1,040 mph) at the equator all the way down to zero at the poles. Even though these relative speeds are slow compared to the speed of light, even something as small as a miscalculated microsecond in the signal’s arrival time can lead to an error in the calculated position by a few hundred meters!

In addition, space curvature lessens as distance from a mass increases, so the satellites are in a weaker gravitational field and experiencing time differently due to general relativity. The combination of these relativistic effects means the clocks on board these satellites should be ticking faster than those on Earth by about 38 microseconds each day, which can add up to big errors after a short time. In order to account for this, GPS satellites are equipped with incredibly accurate atomic clocks and microcomputers that calculate time dilation for the satellites.

Due to their high speeds and orbits, GPS satellites are affected by relativistic time dilation. Source: NASA

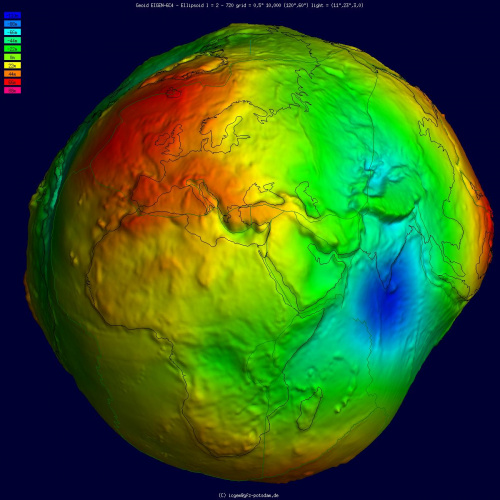

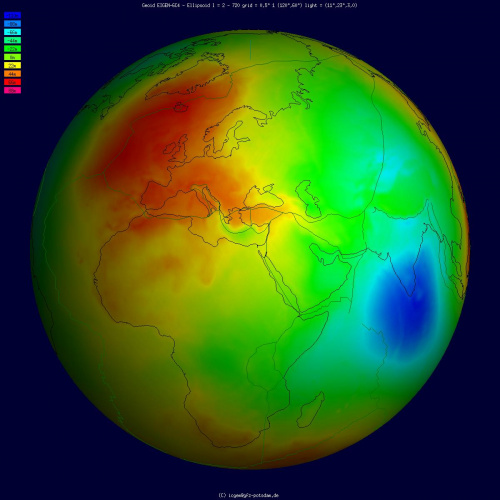

The other obstacle faced by scientists designing the global positioning system was the Earth itself. While it is often approximated as such, the Earth is not a perfect sphere. It's an oblate spheroid shape due to the Earth's rotation, which causes centripetal forces that push material away from the axis of rotation, resulting in a bulge at the equator and a flattening at the poles. In addition to this, oceans, mountains and valleys cause the Earth's surface to be anything but uniform. This means the satellites, although a consistent distance from the Earth's center of mass, are variable distances from the Earth's surface. This can cause errors in the GPS calculations and result in inaccurate location information.

In order to make exact measurements, they needed to have a proper understanding of altimetry, which includes both the height of the planet's surface above sea level and the height of any orbiting satellite above that surface. The Earth’s oceans are massive, and their height changes with time due to tides and other effects like temperature and ice melt. Getting an accurate model of the oceans was imperative to this mission as well.

Geoid undulation in false color, shaded relief and vertical exaggeration (10000 scale factor).

Geoid undulation in false color, to scale.

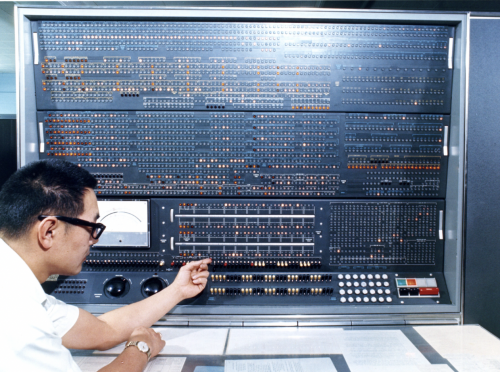

This is where Gladys West came into the picture. From the mid-1970s through the 1980s, West programmed an IBM 7030 Stretch computer to deliver increasingly precise calculations to model the shape of the Earth; "an ellipsoid with additional undulations, known as the geoid." These models accounted for the Earth's shape being distorted by gravitational, tidal, and other forces. Without these calculations, GPS technology would not be able to provide accurate location information, making it much less useful for navigation and other applications.

The IBM 7030 Stretch's console. Source: Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Throughout her career, West was incredibly dedicated to her work. She was tasked with incredibly important and challenging projects, and she is said to have worked long hours optimizing processing algorithms, and cut her team's processing time down by half. She quite literally wrote the guide for the future of radar altimeter satellites by stressing the importance of increasing satellite geodesy's precision with improved technology (check it out to learn more about GEOSAT).

Since her retirement in 1998, Gladys West has continued to be recognized for her contributions to GPS technology and her advocacy for women and minorities in STEM fields. After retiring, she completed a PhD in public administration. In 2018, she was inducted into the Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame for her contributions to the development of the GPS with her accurate geodetic Earth model. Dr. West was nominated and won the award for "Female Alumna of the Year" at the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Awards sponsored by HBCU Digest in 2018 as an alum of Virginia State University. West was selected by the BBC as part of their 100 Women of 2018. In 2021, she was awarded the Prince Philip Medal by the UK's Royal Academy of Engineering, their highest individual honor.

AFSPC Vice Commander Lt. Gen. DT Thompson presents Dr. Gladys West with an award as she is inducted into the Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame.

During her time with the Navy, Gladys West was one of the computers who did the math calculations by hand for these large scale engineering projects before the era of electronic systems. Her work has impacted the world more than she knew was possible when she first started back in 1956. She has said “When you’re working every day, you’re not thinking, ‘What impact is this going to have on the world?’ You’re thinking, ‘I’ve got to get this right.’ ”

Today, West still likes to use a paper map when she travels despite the widespread use of GPS and her integral role in its development. For someone used to trusting their own calculations on paper, some old habits never die.

Learn more about Gladys West from an interview she did with the Navy here:

Want to learn more about GPS? You're in the right place.

- Check out some of our past blog posts to go more in depth on GPS technology.

Head to our GPS resource page to find all you need to know to create your own project inspired by Gladys West.

Head here to shop for our latest and greatest hardware using satellite technology.

If geoids intrigue you and you're in the mood for a geometry-induced headache and a new geometrical coordinate system, take a look at this ESRI post about mean sea level, GPS, and the real shape of the Earth.

Have you used GPS? Thank Gladys West! We want to hear about your work and what women have inspired you through their inventions and hard work. Shoot us a tweet @sparkfun, or let us know on Instagram, Facebook or LinkedIn.